“I hope now we have persuaded [the minister] of the necessity to do extra, not merely to cut back industrial noise however to assist individuals who have suffered industrial deafness. I confess to having some direct and private curiosity within the topic … I’m a type of who has to pin his ear to the amplifier as I’m partially deaf … I attribute this to not advancing years, however to my former industrial expertise within the engineering business.”

Harold Walker was a person obsessive about making work safer. As this extract from a 1983 Home of Commons debate on industrial noise exhibits, the longtime Labour MP for Doncaster didn’t cease campaigning even after his best skilled achievement, the Well being and Security at Work Act, handed into UK regulation 50 years in the past.

Walker was a “no nonsense” politician who introduced his personal experiences as a toolmaker and store steward to tell laws that’s estimated to have saved at the very least 14,000 lives since its introduction in 1974.

However regardless of this, the act has for almost as lengthy been a supply of comedic frustration at perceived bureaucratic overreach and pointless pink tape. The phrase “well being and security gone mad” was frequent parlance within the late twentieth century, and in 2008, Conservative chief David Cameron instructed his occasion convention: “This complete well being and security, Human Rights Act tradition has contaminated each a part of our life … Academics can’t put a plaster on a baby’s grazed knee with out calling a primary support officer.”

Learn extra:

The UK’s Well being and Security at Work Act is 50. Here is the way it’s modified our lives

Such criticisms really feel like a precursor to at this time’s torrent of complaints aimed toward “woke tradition”. However as a senior occupational well being researcher and member of the College of Glasgow’s Wholesome Working Lives Group, I need to arise for this landmark piece of laws, which underpins a lot of our work on extending and bettering working lives – starting from the wants of ageing employees and stopping early retirement as a consequence of in poor health well being, to the results of Lengthy COVID on employee effectivity and psychological well being and suicide prevention at work.

Generally, our group’s analysis highlights modifications to the act which are wanted to suit at this time’s (and tomorrow’s) methods of working. However its basic ideas of employer accountability for security within the office have stood the check of time – and really feel extra related than ever amid the rise of insecure work created by at this time’s zero hours “gig economic system”.

Simon Harold Walker, Creator offered (no reuse)

However my causes for writing concerning the act are private in addition to skilled, as a result of Harold Walker – who in 1997 grew to become Baron Walker of Doncaster – was my grandfather. As a boy, he would inform me terrifying tales about his time working in a manufacturing facility. I didn’t realise that one among them would show to be a seminal second within the formulation of Britain’s trendy well being and security laws.

‘It occurred each fast and gradual’

The small print all the time remained the identical, nevertheless many instances he instructed me the story. His buddy and workmate had been attempting to repair a urgent machine within the toolmaking manufacturing facility the place they each labored. My grandfather vividly painted a scene of maximum noise, sweating our bodies, rumbling machines and soiled faces.

The machine lacked guards and instantly, as his buddy labored, his sleeve bought caught within the cogs. “It occurred each fast and gradual,” my grandfather recalled. He described the person being pulled into the machine, screaming, whereas he and different colleagues tried, unsuccessfully, to wrench him free. Too late, the machine was shut down. By this level, the cogs have been pink with blood, the person’s arm crushed past restore.

Regardless of its apparent culpability, my grandfather stated their employer provided his buddy no help, made no reforms, and easily moved on as if nothing had occurred. My grandfather was deeply affected by the incident, and I imagine it performed a key position in shaping the remainder of his political profession.

Allan Money Image Library / Alamy Inventory Photograph

Walker would function a Labour MP for 33 years, holding roles together with minister of state for employment (1974-79) and deputy speaker of the Home of Commons (1983-92). His fierce help for Doncaster and town’s predominant business, mining, earned him a fame as a key determine in industrial relations – and noticed him battle to keep up neutrality in the course of the 1984 miners’ strike.

As deputy speaker, nobody seems to have been protected from his charismatic if considerably tyrannical rule – he as soon as reportedly chided the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, for straying off-topic. Fellow Labour MP Barbara Fortress described him as “a brief, stocky man who seemed like a boxer and behaved like one on the despatch field – very successfully”.

The act he championed was born from anger and his unshakable perception that employees’ lives have been value defending. Because of his impoverished upbringing – born in Audenshaw close to Manchester, his father had variously been a hat-maker, rat-catcher and dustman – my grandfather was obsessive about ensuring I had correctly becoming footwear, since ill-fitting hand-me-downs as a baby had left his toes completely broken. This perception in small however important acts of care underpinned his method to each life and politics.

How the act was created

For many years after the second world struggle, as Britain sought to rebuild its shattered economic system and infrastructure, a few of its workplaces remained dying traps. In 1969, 649 employees have been killed and round 322,000 suffered extreme accidents. This mirrored, at greatest, a lack of information concerning the want for enhanced employee security – and at worst, a blatant disregard for employees’ well being on the a part of companies and the UK authorities.

For hundreds of years, coal mining had been one among Britain’s most hazardous industries. Miners confronted the fixed menace of mine collapses, fuel explosions and flooding, and disasters comparable to at Aberfan in 1966, the place a coal spoil tip collapsed onto a college killing 116 kids, grew to become tragic markers of the business’s risks. Older miners would usually succumb to illnesses comparable to pneumoconiosis (black lung), brought on by inhaling coal mud day after day.

Likewise, unprotected shipbuilders and dockers, building employees, steelworkers and railway workers all confronted a menace to life merely for doing their job, together with falls from unsafe scaffolding, molten steel accidents and prepare collisions.

Dave Bagnall Assortment/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Within the textile mills of Manchester and past, employees toiled in poorly ventilated factories, inhaling cotton mud that led to byssinosis, or “Monday fever”. Poisoning and publicity to harmful chemical compounds plagued employees in tanneries and chemical vegetation.

Whereas the 1952 London smog had introduced nationwide consideration to large-scale respiratory illnesses when some 4,000 extra deaths have been recorded over a fortnight (resulting in the primary efficient Clear Air Act in 1956), respiratory illnesses within the office have been sometimes thought-about simply one other occupational hazard in any business that concerned mud or poisonous fumes, from mining to shipbuilding to textiles. In the meantime one other lurking, silent killer – asbestos in buildings – would solely be recognised within the late twentieth century as the reason for lethal circumstances comparable to mesothelioma.

Learn extra:

The hidden hazard of asbestos in UK faculties: ‘I do not suppose they realise how a lot threat it poses to college students’

Historian David Walker has argued that many British firms favoured reparations over prevention as a result of it was less expensive, leading to hundreds of employees completely being disabled and unable to work. Decided to vary this systemic injustice, Walker first revealed his ambition to herald new protections for employees in 1966, when he proposed “some obligatory amendments to the Factories Acts”. However progress was gradual and troublesome.

Over time, each time my grandfather instructed me about these parliamentary debates and personal arguments whereas digging his backyard in Doncaster, I swear he would stick his fork into the earth extra forcefully. His tales have been stuffed with names like Barbara Fortress, Michael Foot, Philip Holland and Alfred Robens that meant little to me as a boy. However even to my younger self, it was apparent the creation of the act required extraordinary ranges of dedication and resolve.

The Insights part is dedicated to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with teachers from many alternative backgrounds who’re tackling a variety of societal and scientific challenges.

In 1972, the Robens Report – commissioned by Fortress, then Labour’s secretary of state for employment and productiveness – laid extra concrete groundwork by calling for a single, streamlined framework for office security. Working alongside authorized consultants, business leaders and union representatives, my grandfather was a central a part of the staff trying to translate these suggestions into sensible regulation. A lifelong smoker, he painted vivid footage to me of the infinite debates in smoky committee rooms, poring over drafts late into the night time.

This was a cross-party effort involving MPs and friends from all sides, united by a shared dedication to deal with appalling office circumstances, who confronted important opposition each inside and out of doors the commons. Regardless of this, the act’s journey by means of parliament was something however easy – beset by disagreements over small particulars or questions of course of, comparable to when a 1972 debate veered off target to debate the nuances between “occupational well being” and an “occupational well being service”.

In Could 1973, Liberal chief Jeremy Thorpe taunted his parliamentary colleagues concerning the lack of progress on the act, shouting throughout the ground at Dudley Smith, the Conservative under-secretary of state: “Nobody would need the honourable gentleman to sit down there pregnant with concepts, however constipated about giving us any indication of what was supposed.”

One of many thorniest points was whether or not the regulation ought to prescribe particular guidelines or take a broader, principle-based method. The latter would finally win out, mirrored within the now-famous phrase “as far as within reason practicable”, which means employers should do what is possible and smart to make sure the well being and security of their employees. Because the invoice was learn but once more in April 1974, Walker – by now the under-secretary of state for employment – was congratulated on his dogged dedication by opposition Tory MP Holland:

“The honourable member for Doncaster has spent a lot effort and time on this topic in earlier debates that it’s becoming he ought to now be in his current place to see this invoice by means of its numerous phases … On this invoice, now we have such a broad method to the topic, and I welcome it on these grounds. The actual fact the final two common elections interrupted the promotion of security laws causes me somewhat trepidation concerning the destiny of this invoice. However I hope this parliament will final lengthy sufficient to see it attain the statute e book.”

Well being and security ‘goes mad’

When it lastly handed into regulation in July 1974, the Well being and Security at Work Act aimed to make sure each employee had the suitable to a protected atmosphere. It launched a basic shift in accountability, making employers accountable for their workers’ welfare by means of monetary penalties and public discourse, and established an unbiased nationwide regulator for office security, the Well being and Security Government.

Two years later, when requested in parliament if he was glad with how the act was working, Walker replied: “I shall be glad with the operation of the act when I’m certain that every one folks at work – employers, workers and the self-employed – are taking all obligatory measures for their very own and others’ well being and security.”

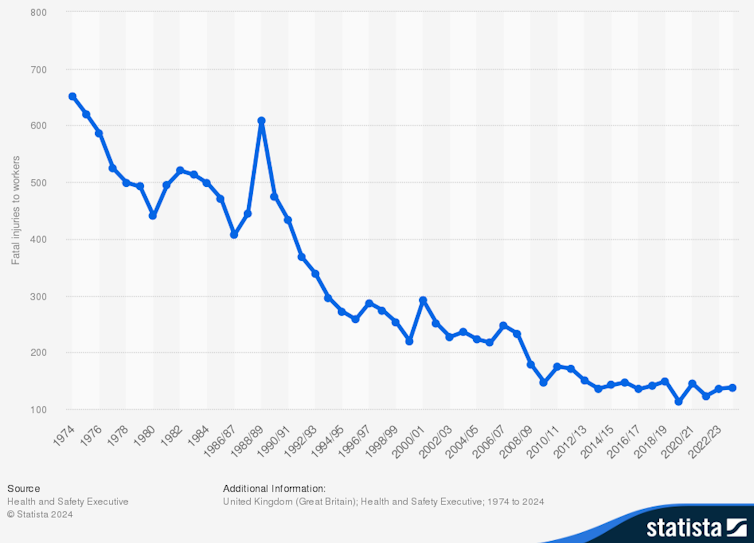

Because the act’s inception, the variety of office deaths in Britain has fallen from almost 650 a yr within the Nineteen Sixties to 135 in 2023. This decline is much more placing when contemplating the parallel progress within the UK workforce, from 25 million in 1974 to greater than 33 million at this time.

Variety of deadly accidents to employees in Nice Britain, 1974-2024:

D Clark/statista.com, CC BY-NC-ND

Severely injured employees may now obtain incapacity advantages or compensation funded each by the state and their employers. The act changed the Workmen’s Compensation Act (1923), which had favoured employers, nevertheless it nonetheless positioned a heavy burden on employees to show their sickness was brought on by their work. Because of this, the outcomes of claims assorted considerably relying on particular person circumstances.

Virtually instantly, the act attracted criticism each for each going too far, and never far sufficient. In March 1975, the Each day Mail revealed a full web page “advertorial”, issued by the Well being and Security Fee, headlined “A Nice New Likelihood to Make Work a Lot Safer and More healthy – for everybody in Britain”. However by September, the identical newspaper was mounting a scathing assault on the brand new Well being and Security Government (HSE) beneath the headline “The Nice Crimson Tape Plague”, which ended with a quote from an employer saying: “New guidelines are made so quick today that it takes me all my time to implement them. I’m critically contemplating giving up.”

The HSE, a largely bureaucratic physique, shortly launched an more and more sophisticated system of checks and balances by means of which employers have been questioned by inspectors in an effort to shield employees – a system that, in time, the act grew to become closely criticised for.

Excessive-profile circumstances of seemingly trivial bans or excessive precautions – comparable to forbidding conker video games with out goggles in faculties and cancelling native traditions over legal responsibility fears – have been usually ridiculed within the media and by critics of forms, who framed them as proof of a creeping “nanny state” tradition that stifled frequent sense and private accountability. This prolonged to public well being campaigns such because the push for obligatory seatbelt-wearing, which induced the Each day Mail to quip in 1977: “Those that need to enslave us all, to the Left …”

The “nanny state” criticism caught, and has change into lodged in our common tradition. A long time later, Conservative employment minister Chris Grayling compiled an inventory of the highest ten “most weird well being and security bans”. High of his checklist of examples of “well being and security gone mad” was an incident wherein Wimbledon tennis officers cited well being and security considerations as the rationale for closing the grassy spectator hill, Murray Mount, when it was moist. Grayling complained:

“We now have seen an epidemic of excuses wrongly citing well being and security as a motive to stop folks from doing fairly innocent issues with solely very minor dangers connected.”

Phrases like nanny state, woke and cancel tradition are actually used interchangeably to criticise perceived over-sensitivity, entitlement, or self-serving and inauthentic types of activism. In November 2024, the GB Information web site revealed an article referring to the set up of security warnings on staircases at Cambridge College as “utter woke gibberish!”

However defenders of well being and security level out that many of those examples are, the truth is, misinterpretations of the act, pushed extra by organisations’ fears of litigation than by authorities regulation. Within the wake of Grayling’s high ten checklist, Channel 4 debunked the claims about sponge footballs and banned sack races, noting that such tales have been not often linked to the act itself.

The strain between obligatory protections and perceived overreach has change into emblematic of broader debates about state intervention, accountability and threat in trendy Britain. In June 2024, a survey of greater than 1,200 frontline employees throughout six sectors discovered that seven in ten employees suppose rules gradual them down. But greater than half (56%) agreed that that they had risked their well being and security at work, with 1 / 4 (27%) having carried out so “a number of instances”.

The rise of the gig economic system

The Well being and Security at Work Act, although up to date a number of instances – and with a brand new modification on violence and harassment within the office) now being debated – is frequently examined by the emergence of latest forms of job and methods of working.

The rise of gig work, automation, and precarious contracts has sophisticated conventional notions of office security. The gig or freelance economic system has created a tradition of short-term unaffiliated employees starting from cleaners to tutorial tutors to e-bike driving deliveries. These employees sometimes lack any type of occupational well being help. Sick days imply misplaced wages and potential lack of jobs sooner or later.

Andy Gibson/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Throughout the COVID pandemic, a survey of 18,317 folks in Japan discovered that gig employees had a considerably greater incident price of minor occupational and activity-limiting harm, in contrast with their non-gig working counterparts.

An enormous query for regulators such because the HSE to deal with is round accountability. Since gig employees are thought to be self-employed, they sometimes bear the well being and security accountability for themselves and anybody who’s affected by their work, quite than their employer. Within the UK, their rights have been considerably strengthened by a 2020 excessive courtroom ruling that discovered the federal government had didn’t implement EU well being and security protections for short-term (gig) employees.

Well being and security laws has been made much more advanced by the adoption of latest applied sciences and, now, synthetic intelligence. In 1974, when the UK act was launched, computer systems have been very a lot of their infancy, whereas in 2024, hundreds of thousands of employees have exchanged desk dependency for the obvious freedom to work anyplace by means of telephones, tablets and computer systems.

A selected subject for the UK authorities (and all sectors of the economic system) is why so many individuals, significantly older employees, are inactive as a consequence of long-term illness. Not solely is that this dangerous for enterprise, it’s dangerous for society too. Waddell and Bell’s influential 2008 report, Is Work Good on your Well being and Wellbeing?, made the case that the dangers of being out of labor have been far greater than the dangers being in work.

A rising physique of proof suggests well being interventions ought to transcend the remit of the unique act by participating with employees extra holistically, each inside and out of doors conventional workplaces, to assist them keep in work. One intervention examined by our Wholesome Working Lives Group discovered that illness absence might be decreased by a fifth when a telephone-based help programme for restoration was launched for employees who have been off sick.

The trendy flexibility of working areas has blurred the boundaries between work and personal spheres in methods that may create extra stress and well being dangers – for instance, for employees who by no means absolutely cease working due to electronic mail tethers. That is the world of labor which future variations of the act should handle.

My grandfather’s legacy

Simon Harold Walker, Creator offered (no reuse)

My grandfather died in November 2003 once I was 19, so my reflections on why he made well being and security his life’s work come partly from unpublished papers I discovered after his dying, in addition to Hansard’s experiences of his strong debates within the Home of Commons. For him, it was an ethical crucial – demonstrated by the truth that he continued to problem the very act he had helped create, critiquing it for not doing sufficient to guard employees.

Walker’s regrets over the act have been poignantly revealed in December 2002, in one among his final contributions to the Home of Lords earlier than his dying, when he drew from his pre-politics experiences to problem calls to ease rules on asbestos at work:

“I’ve asbestos on my chest – for many of my grownup life previous to coming into parliament within the Nineteen Sixties, I labored in business with asbestos, principally white asbestos. Within the Nineteen Sixties, once I was a junior minister, I used to be concerned within the dialogue of the rules regarding asbestos. The talk thus far at this time has carried echoes of [those] discussions, once I was persuaded we should always not legislate as rigorously as we’d have carried out as a result of the hazards had not been absolutely assessed. Are we happening that highway once more?”

Maybe predictably, tributes after my grandfather’s dying mirrored the curious confusion that his well being and security laws had aroused in British society. Labour MP Tam Dalyell praised him as “the best champion of office security in trendy British historical past”. In distinction, parliamentary journalist Quentin Letts ranked him forty sixth amongst folks to have “buggered up Britain” – he was demoted to 53rd in Letts’s subsequent e book – because the architect of a regulatory system that destroyed the industries it sought to guard. In his obituary, Letts wrote:

“Harold Walker, the grandfather of the HSE, usually meant effectively. However that’s not fairly the identical as saying that he achieved good issues. Not the identical factor in any respect.”

My grandfather would have been the primary to argue that the act was not excellent, as a result of compromise doesn’t lend itself to perfection. However as I see in my analysis at this time, it modified the world of labor and well being by shining a essential mild on employees and employers. In some ways, it led the cost for employees security – the European Framework Directive on Security and Well being at Work was solely adopted a lot later, in 1989.

Had been he nonetheless alive, I believe he would agree with Letts about a few of the unintended penalties of the act. However I additionally suppose he would give quick shrift to trendy debates concerning the nanny state and wokish over-interference – dismissing these as “people whinging”, accompanied by a attribute roll of his eyes.

My grandfather believed his laws was not merely about compliance, however about fostering a tradition the place security grew to become systemic and instinctive. Tales of “well being and security gone mad” have obscured his act’s true function – to vary how all of us take into consideration our tasks to 1 one other. I hope we’re not dropping sight of that.

For you: extra from our Insights sequence:

To listen to about new Insights articles, be a part of the a whole bunch of hundreds of people that worth The Dialog’s evidence-based information. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.