Within the spring of 2024, residents of the south Devon harbour city of Brixham saved falling unwell. Their signs – together with “terrible abdomen complaints, dangerous diarrhoea and extreme complications” – went on for weeks. A retired GP who ventured to the pub after lastly recovering from the sickness recalled that, when somebody requested these current to “elevate their hand in the event that they hadn’t had the bug”, not a single hand went up.

Given the controversies about uncooked sewage discharges that had been swirling on the time, the ingesting water appeared an apparent suspect. Many native residents contacted their water supplier, however by late April, South West Water was nonetheless insisting the water was protected to drink, and that each one checks for contaminating micro organism had returned adverse.

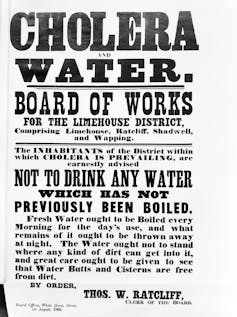

Then immediately, the corporate issued an pressing “boil it” be aware to 1000’s of households in Brixham and close by villages and cities within the Torbay area. A tiny parasite that causes the intestinal illness cryptosporidiosis had been found within the water provide.

The contamination was ultimately pinpointed to a faulty valve below a stretch of farmland which had allowed cow faeces to enter three holding tanks of ingesting water – downstream from the primary water works, and likewise from the place the water’s high quality was routinely examined.

In line with South West Water, the outbreak finally affected 17,000 households. Whereas the official document reveals 77 confirmed circumstances of “crypto”, as it’s generally identified, the UK Well being Safety Company solely started surveying residents within the second week of July – lengthy after the outbreak started.

The contamination of a whole area’s water provide, with 1000’s of households pressured to depend on bottled water or boiling their faucet water for months, is surprising. However as consultants within the historical past of waterborne illness outbreaks and public well being, what considerations us most is how shortly the story has moved on – as if nothing may very well be finished and it was “simply one other an infection”.

Given the UK was as soon as identified for its revolutionary sanitation initiatives, we need to perceive what systemic points – from insufficient infrastructure to company cover-ups to lax laws – lie on the coronary heart of this incapability to maintain the water clear and folks free from waterborne an infection. Or put one other means: why can’t Britain get its shit collectively?

The residents of Torbay have a selected proper to ask this query. In the summertime of 1995, the identical Devon vacation area (referred to as the “English riviera”) skilled the UK’s first main outbreak of waterborne illness – additionally cryptosporidiosis – because the water business was privatised by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative authorities in 1989. Greater than 250,000 residents had been despatched a “boil it” discover. By the top of the summer season, there had formally been 575 circumstances and 25 hospitalisations.

A 12 months later, the setting secretary John Gummer took South West Water to courtroom below part 70 of the 1991 Water Business Act. This was the primary time a British water firm had been taken to courtroom for offering water unfit for human consumption – however the case was thrown out after proof offered by the Ingesting Water Inspectorate was dominated inadmissible.

The ruling fuelled public fears that water corporations, like different newly privatised state enterprises, couldn’t be held correctly accountable for his or her mismanagement. These considerations have grown over the following three a long time, as South West Water – and England and Wales’s different 9 personal water and sewage corporations – have frequently been accused of prioritising wholesome shareholder dividends over the general public’s well being.

This text is a part of Dialog Insights.

Our co-editors fee long-form journalism, working with lecturers from many various backgrounds who’re engaged in initiatives aimed toward tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Lots of the world’s fashionable methods of public well being surveillance have their origins in improvements Britain launched within the mid-Nineteenth century, together with steady water provide, sewage filtration and routine governmental investigation of illness outbreaks.

And but Britain has by no means managed to eradicate systemic failures in the case of offering protected, clear and accessible ingesting water to its residents. To know why not, we have to begin by revisiting Britain’s main cholera and typhoid outbreaks of the Nineteenth- and early Twentieth-century, which at their peaks killed tons of of individuals every single day.

‘The ability of life and dying’

The colossal energy of life and dying wielded by a water firm supplying half one million prospects is one thing for which, until just lately, there was no precedent within the historical past of the world. Such an influence ought most sedulously to be guarded towards abuse.

These prophetic phrases had been written by the British authorities’s first ever chief medical officer, John Simon, in 1867. He was responding to one of many nation’s worst water-related scandals: the 1866 cholera epidemic that killed 5,596 individuals within the East Finish of London.

Wellcome Assortment, CC BY-NC-ND

A authorized mechanism ought to have prevented this appalling lack of life. In line with the 1852 Metropolis Water Act – launched in response to earlier cholera epidemics within the 1830s and 40s that had additionally killed 1000’s – London’s eight personal water corporations had been compelled to maneuver their river water intakes away from the polluted metropolis centre (the place the river was nonetheless tidal), and to carry out water filtration earlier than it reached customers. But the act was powerless to forestall the return of cholera in June 1866, this time due to the failings – and denials – of the East London Water Firm.

Inside weeks, the epidemic was killing tons of of Londoners every single day. Holborn’s medical officer of well being, Septimus Gibbon, reported the deaths of two youngsters on the identical day on the house of a cigar maker in Cannon Avenue, observing:

The home the place these youngsters resided is in clear and truthful sanitary situation, however there’s an outdated and partly disused sewer working shut behind it, within the rear of Nice James Avenue, which the sanitary authority is unable to destroy, as a result of three homes in Inexperienced Avenue declare a proper to empty into it.

On the peak of this cholera outbreak, the East London Water Firm denied all accusations from authorities epidemiologists that it was accountable for the deaths. In August 1866, the corporate’s chief engineer, Charles Greaves, wrote a letter to The Instances declaring that, for a number of years, “not a drop of unfiltered water has been provided by the corporate for any goal”. However his assertion was shortly contradicted by two native residents, who instructed the East-Finish Information that they had found eels of their water pipes.

Ultimately, pioneering epidemiologists found that the East London Water Firm – wrestling with each a blocked water filter and unusually excessive demand in early June 1866 – had opened the sluice at its uncovered Outdated Ford reservoir, drawing in unfiltered water and unleashing diarrhoeal horrors on the residents of east London.

But regardless of being in clear violation of the 1852 act, the corporate argued different components had been accountable for the cholera outbreak – even together with the suspect morals of East Finish residents. In his proof to a parliamentary choose committee, engineer Nathaniel Beardmore pointed to the risks of an overcrowded East Finish “populated by dock labourers, sailors, mechanics within the new factories, and nice numbers of laundresses”.

Finally, whereas the East London Water Firm obtained a number of dangerous press, it was given no official sanctions. A sample of denial and obfuscation had been established that water corporations have frequently employed ever since, when accused of being accountable for life-threatening water infections.

‘Useless our bodies are being washed ashore’

Within the wake of the 1866 cholera outbreak, Simon, the pioneering chief medical officer, argued that the way in which to eradicate lethal well being outbreaks was a mix of extra surveillance of water corporations and extra preventive public well being measures based mostly on epidemiological investigations. This is able to imply fastidiously monitoring illness information from across the nation, and sending in epidemiological consultants on the first signal of disaster – not ready till after an outbreak had exploded.

However regardless of Simon’s urgings, it could take one other surprising water-related scandal for the British authorities to get critical in regards to the risks of untreated sewage.

Wikimedia Commons

One late-summer night in September 1878, the Princess Alice, a paddle steamer with greater than 800 individuals on board, smashed into the coal ship Bywell Fortress in the midst of the River Thames. The Alice was just about sliced in two, and sank inside minutes in sight of North Woolwich pier.

Two hours earlier, 75,000 gallons of uncooked sewage from the outflows of Joseph Bazalgette’s much-heralded underground sewerage system – constructed to rid London of its “nice stink” and solely simply accomplished – had been discharged into the identical stretch of river, forming a noxious cloud of air and hideously contaminated water. A survivor of the catastrophe would later recall:

Each the style and scent had been one thing dreadful … Having been all the way down to the underside and having rose once more with my mouth stuffed with it, I might give an excellent image of it – it was probably the most horrid water I ever tasted and the scent was additionally equally dangerous.

This was Britain’s worst inland waterway tragedy, claiming round 650 lives. A report in The Instances described useless our bodies “frequently being washed ashore alongside the entire course of the river from Limehouse to Erith … It is going to be some days earlier than this rendering up of the useless shall be at an finish.”

Whereas the victims died by drowning or asphyxiation as a result of being trapped contained in the sinking boat, the descriptions of the state of the river water and air precipitated outrage among the many public. In response, the federal government rushed in a brand new legislation that each one sewage have to be handled earlier than being discharged into rivers. In depth new therapy services had been commissioned, starting in east London, and a Royal Fee on Sewage Disposal was established in 1898 – the primary to set official requirements for the therapy of wastewater.

However whereas these efforts meant the specter of cholera was largely eradicated from British ingesting water, its lethal waterborne cousin, typhoid fever, continued to wreak havoc. So prolific had been these outbreaks – together with the worst episode of typhoid in fashionable British historical past, when almost 2,000 individuals had been contaminated and greater than 140 died in Maidstone, Kent, in 1897 – that by the flip of the century, greater than 150 British cities and cities had taken duty for offering and regulating water into their very own arms.

Maidstone Museum/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-ND

This new imaginative and prescient of municipal duty was encapsulated by the pioneering mayor of Birmingham, Joseph Chamberlain, who spearheaded an enormous public possession programme for provision of fuel, colleges, libraries and metropolis parks. In 1876, he established the Birmingham Company Water Division after shopping for the personal Birmingham Waterworks Firm for £1,350,000 (over £195 million at at the moment’s costs).

Progressives argued that eradicating personal business from the availability of water and different key companies would make sure the requirements of well being and hygiene that fashionable cities and cities required – and that this was extra essential than firm earnings. Or as Chamberlain put it:

We now have not the slightest intention of constructing revenue … We will get our revenue not directly within the consolation of the city and within the well being of its inhabitants.

The march of municipalisation

Maidstone’s lethal typhoid outbreak would see the city go down in historical past because the world’s first municipality to aim widespread water sterilisation, when its reservoir and mains water provide had been disinfected with an answer of chloride of lime in 1897 (it proved “a tough process that required a number of makes an attempt”). In time, this initiative would result in international water chlorination programmes which can be estimated to have saved thousands and thousands of lives by stopping the unfold of harmful micro organism together with Salmonella Typhi, the reason for typhoid fever.

Shortly afterwards, in 1902, London joined the march of municipalisation, when the Metropolitan Water Act created the biggest public water system in Britain with the acquisition of town’s personal corporations. The East London Water Firm alone was bought for almost £4 million – over £600 million at the moment.

The rationale was threefold: price financial savings from supply at scale, an ethos of civic duty, and the assumption that publicly owned water may very well be extra intently monitored, stopping waterborne outbreaks sooner or later.

By the mid-Twentieth century, a public-private hybrid was the norm for water provision in Britain – and the dimensions of the ensuing public investments in waterworks was staggering. Nonetheless, the argument that these would result in long-term financial savings was disputed – with a 1920 parliamentary committee on the influence of the Metropolitan Water Act concluding:

Not solely has there by no means been any financial savings in complete price, [but] the precise expenditures of the [new London-wide water] board have been in extra of the entire of the eight undertakings whose properties had been taken over. The price of the water provides … has risen.

Municipal water initiatives could not have saved cash, however did they save lives? A 2016 research discovered that municipalisation of Britain’s water provide from the late-Nineteenth century resulted in a discount of typhoid fever by 19%. The town of Oxford skilled an preliminary decline in typhoid mortality from the Eighteen Eighties as a result of improved sand filtration and municipal piped water, adopted by a pointy decline when chlorination of the water was launched in 1930.

And but, within the second half of the Twentieth century, sewage therapy throughout Britain persistently failed to satisfy the requirements demanded by legal guidelines imposed a long time earlier, in accordance with a report by the federal government regulator Ofwat:

The will to get rid of sewage as cheaply as doable led to a scarcity of funding in sewage therapy by many councils, and the variety of river air pollution incidents elevated via the Sixties. This, in flip, elevated the therapy requirement of river water abstractions. By the top of the Sixties, 60% of all sewage therapy works had been estimated to be failing to satisfy the requirements established on the finish of the Nineteenth century.

Thatcher’s radical technique

By the early Nineteen Seventies, England and Wales nonetheless possessed a motley crew of private and non-private methods for coping with sewage and water. In all, there have been 160 completely different water corporations (some public, some personal), 130 sewerage authorities, and 29 river authorities. The place operational dangers had been normally shouldered by the personal sector, the general public sector usually carried all of the (huge) monetary dangers related to the constructing of water therapy infrastructure.

In 1973, Edward Heath’s Conservative authorities sought to finish this complicated array of localised water and sewerage provision. Its newest model of the Water Act established ten new regional water authorities – based mostly not on the political would possibly of cities however the dominant regional river methods in England and Wales. It was an formidable however largely smart try to safe the long-term well being of Britain’s water provide. In early February 1973, Geoffrey Rippon, secretary of state for the setting, instructed his Home of Commons colleagues:

It is a radical reconstruction. I counsel it’s none the more serious for that. It takes its place alongside the reorganisation of native authorities and of the well being companies on this authorities’s overhaul of the administration of the nation, to maintain tempo with the issues with which we will need to deal via the remaining a long time of this century and into the subsequent.

Rippon was searching for approval for a programme of fastidiously coordinated private and non-private funding – however his plea fell on deaf ears amongst Conservative MPs and their colleagues throughout the aisle. As a substitute, a extra radical technique was launched by Heath’s successor as Tory chief, Margaret Thatcher.

Reasonably than investing any extra public cash in Britain’s water infrastructure, Thatcher sought to place Britain’s complete system of water provision again within the arms of the personal sector. A decade after she got here to energy in 1979, and regardless of a public outcry and plenty of referendums, she lastly achieved this via the Water Act of 1989. This turned the regional water authorities in England and Wales into restricted corporations, and provided profitable regional monopolies to the best bidders. (In Scotland, the plans to privatise had been met with significantly robust opposition, and its public schemes stay to at the present time.)

Derek Copland/Alamy Inventory Photograph

In a single notorious speech within the Home of Commons, Thatcher’s argument rested on a simplistic financial case for long-needed funding: “It is going to be the individuals who need these enhancements in water who should pay.”

This was a reversion again to the Victorian origins of Britain’s strategy to water provision. However the prime minister had orchestrated her case nicely. Restrictions imposed by her authorities on public borrowing because the early Eighties had made it unattainable for the regional water authorities to borrow cash for investments for over a decade.

On the identical time, the Eighties noticed a steadily rising concern for the setting among the many British public and rising demand for enchancment of its waterways. The UK’s embarrassing failure to satisfy European obligations which it had co-designed made privatisation appear to be a smart final resort, though such a coverage had no priority in another developed nation.

But it remained one of the crucial unpopular coverage selections of the Thatcher authorities. In 1994, the Each day Mail – normally an ardent supporter of the Conservative occasion – condemned it below the headline “The Nice Water Theft”, declaring:

When it was privatised in 1989, the water business was hailed because the jewel within the crown of the Thatcherite privatisation programme … In actuality, the water business has grow to be the largest rip-off in Britain. Water payments, each to households and business, have soared. And the administrators and shareholders of Britain’s top-ten water corporations have been ready to make use of their place as monopoly suppliers to tug off the best act of licensed theft in our historical past.

Globally, the full-scale water privatisation of England and Wales stays an exception, aside from for a couple of World Financial institution-led initiatives in creating economies. Most European nations have opted for a coexistence of personal and public our bodies.

In England and Wales, promoting off water suppliers as regional monopolies led to unsustainable value hikes, with firm after firm prioritising shareholders over prospects from the get-go. Whereas publicised funding methods implied that sewerage methods had, on common, a dependable lifetime of 280 years, in actuality many are crumbling away – with even conservative evaluations limiting their lifetime to about 110 years, such that some pressing upgrades are actually urgently wanted.

‘Poisoned customers’

In the summertime of 1995, when Torbay skilled the UK’s first main outbreak of a waterborne parasite since Thatcher’s privatisation programme, investigations by Public Well being England traced the outbreak to the Littlehempston water therapy facility close to Totnes – however there was no conclusive proof on how the cryptosporidium parasite had entered the water.

South West Water provided £15 to every affected family, however claims of reputational and financial injury from the outbreak had been rising by the hour. Authorized motion towards the corporate adopted however the case was thrown out. After putting in a brand new filtration system, South West Water said it had “completely minimised” any future danger of a abdomen bug rising from the defective facility. But as litigation had been unsuccessful, there was no pathway to check this pledge and maintain the corporate to account for any future failures.

The acquainted cop-out of downplaying the seriousness of any faults – whether or not in monitoring and regulating water high quality, or a scarcity of funding in infrastructure – was voiced once more in March 1997 by Conservative MP James Clappison, who famous throughout a debate on cryptosporidium that “most incidents are comparatively minor happenings”.

Earlier that very same month, Thames Valley Water had issued one other dreaded “boil it” discover, this time to 300,000 prospects in Hertfordshire and North London. Emboldened by the failed authorized case in south Devon, the corporate robustly refused compensation claims and provided a single paltry payout of £10 to affected prospects.

In Scotland, in the meantime, water had been retained in public possession. Writing in The Scotsman in March 1997, columnist Lesley Riddoch remarked that in England and Wales, there was clearly “nonetheless no authorized requirement for corporations to compensate poisoned customers”.

Following Tony Blair’s landslide victory in Could 1997, the brand new Labour authorities promised tighter oversight of the water business – together with an elevated risk of prosecution for corporations that transgressed. However for Adrian Sanders, then Torbay’s LibDem MP, this didn’t go far sufficient, as he instructed the native Herald Specific newspaper in Could 1998:

I’m involved there nonetheless isn’t something to permit impartial watchdogs entry into water remedies for checks. There isn’t a clearcut means for residents to hunt compensation if they’re the victims of the bug.

Within the 12 months following Blair’s election, all ten of England and Wales’s water and sewerage corporations had been discovered responsible of environmental offences. Thames Water and Anglian Water had been prosecuted eight occasions in 1999, and by 2001, Severn Trent led the “serial offenders” desk with 494 air pollution incidents because the new authorities got here to energy. However the related fines had been normally negligible. Wessex Water, a subsidiary of US vitality firm Enron, was fined solely £5,000 (plus prices) for discharging 1 million gallons of uncooked sewage into Weymouth marina in Dorset one August financial institution vacation.

Extra just lately, government-induced fines have elevated. Since 2015, the UK Atmosphere Company has prosecuted 59 water and sewerage corporations for over £150 million. But outbreaks of waterborne diseases from dodgy, stinking, and contaminated water sources stay all-too-common. In Could 2024, Conservative MP Anthony Mangnall condemned South West Water’s response to the outbreak of cryptosporidium in his south Devon constituency:

I feel that is contemptible and simply typically incompetent – it’s put lots of people’s well being in danger. That, to me, is among the most critical indictments as a result of they had been made conscious of this by a lot of individuals, together with myself … So to not really reply in a way that may safeguard public well being, I feel, is deeply problematic.

nidpor/Alamy Inventory Photograph

Is Britain’s water system damaged?

Within the period of COVID-19, we principally hear about epidemiology because the science of predictive modelling. However at its core, epidemiology is a detective science of outbreak investigation. This implies finishing up correct diagnoses to confirm the sample of an outbreak, make clear the presence of a standard infective agent, elucidate circumstances which may speed up the epidemic, then type a speculation about its trigger.

But outbreak investigations appear too typically to be a factor of the previous. “The closest I heard of any surveys,” one Brixham resident famous earlier this 12 months, “was post-Pilates espresso conversations: have you ever had the bug?”

As the sooner, failed authorized problem towards South West Water in 1996 recollects, to develop a profitable prosecution, a case wants good detective work involving up-to-date water monitoring in addition to epidemiologists on the bottom, counting circumstances.

In Keir Starmer’s first prime minister’s questions on July 24, the very first query posed – by Calum Miller, LibDem MP for Bicester and Woodstock – challenged the brand new prime minister to simply accept that “Britain’s water system is damaged”.

The brand new authorities – in echoes of the Blair ministry nearly 30 years earlier – had already promised within the king’s speech to strengthen the powers of the water regulator Ofwat, enhance compensation ranges for “boil it” notices, and make it simpler for patrons to carry water firm bosses to account in particular hearings. These measures level in the precise path, however they received’t go far sufficient to revive belief in British water after so many a long time of failure.

Nearly 150 years on from the unique “march of munipalisation” led by Birmingham’s Mayor Chamberlain and different cities and cities, the company standing of British water suppliers is again below scrutiny. Whereas the brand new Labour authorities formally has no plans to re-nationalise Britain’s water, we’re squarely again in conversations about whether or not Britain’s finest guess with water security is a extra draconian regulation of privatised corporations, or a return to nationalisation.

With Thames Water in misery and steep value hikes forward, it is a tough political and financial gamble for the federal government and the water regulator. However even when the federal government finally ends up having to take some corporations into “particular measures”, this received’t tackle the overwhelming subject of a leaking, ailing and stinking water and sewerage infrastructure that’s unfit for goal.

If the way forward for water corporations continues to be personal, public or someplace in between (which appears most certainly), a key query is how you can preserve public and political will for infrastructure investments on the large scale that’s required – amid the “black gap” in public funds recognized by the chancellor Rachel Reeves.

However making certain protected and clear water additionally requires sooner epidemiological investigation and new monitoring methods. When issues go flawed (and the subsequent crypto outbreak won’t be distant), affected prospects require a correct outbreak investigation – not tokenistic compensation and lukewarm guarantees from their water supplier.

Epidemiological evaluation ought to start as quickly as a failure is observed – not like at Brixham earlier this 12 months, the place a correct survey solely started 9 weeks after the “boil it” notices had been despatched out. Investigations carried out too late danger changing into complicit in any try to cowl up the dimensions of a water disaster.

A greater future is dependent upon correct outbreak investigation in live performance with acceptable laws, which gives the possibility to supply true accountability. If proof collected in well timed vogue by an impartial company stands up in courtroom, authorized routes to compensation grow to be a viable choice for patrons. This in flip ought to present a substantial motivation for water suppliers – personal or in any other case – to lastly begin cleansing up their shit.

For you: extra from our Insights collection:

To listen to about new Insights articles, be a part of the tons of of 1000’s of people that worth The Dialog’s evidence-based information. Subscribe to our publication.

.jpeg?width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800&w=120&resize=120,86&ssl=1)